A Case Study

of Aroland First Nation, Arthur Shupe Wild Foods,

Nipigon Blueberry Blast Festival, and the Algoma Highlands Wild Blueberry Farm and Winery

September 2017

William Stolz, Charles Z. Levkoe and Connie Nelson

This work was made possible through generous funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Suggested citation:

Stolz, W., Levkoe, C.Z. and Nelson, C. 2017. Blueberry Foraging as a Social Economy in Northern Ontario: A Case Study of Aroland First Nation, Arthur Shupe Wild Foods, Nipigon Blueberry Blast Festival, and the Algoma Highlands Wild Blueberry Farm and Winery. Centre for Sustainable Food Systems, Wilfrid Laurier University.

Preamble – The Social Economy in Northwestern Ontario

“…much of the traditional economy of indigenous societies can be considered part of the social economy in that much of its pre-capitalist values still play an important role in the region and act in contradiction to the profit seeking values of contemporary society.”

— Abele and Southcott (2007)

The social economy, which places ‘people before profits’ arose from a failure of contemporary political and economic policies to provide minimum acceptable levels of economic and social wellbeing to people (Restakis, 2006). The failure of mainstream economic theory and practice to address these problems is a reason for the increased interest in new strategies and paradigms that are more just, equitable, and responsive to the needs of society, and not just a privileged minority (Restakis, 2006). Lewis and Swinney (2007) highlight the importance of reciprocity in the social economy: “The primary purpose of social economy organisations is the promotion of mutual collective benefit. The aim of reciprocity is human bonding or solidarity. In contrast to the private sector principle of capital control over labour, reciprocity places labour, citizens, or consumers in control over capital” (p. 11). Forest foods, which include tree sap, mushrooms, nuts, plants, and berries are highly valued by Indigenous communities and other forest food harvesters as a source of income, food security, tradition, and as an alternative to timber extraction on Crown land (Milne, 2013). Foraging for forest foods is an adaptable way to achieve food security in the boreal forest (Milne, 2013), with a plethora of different foods and value-added products such as jam available that can be stored year-round.

Many Indigenous communities still participate in a traditional economy to achieve food security and as part of their cultural identity. Kuokkanen (2011), who uses the terms traditional and subsistence economies interchangeably, explains that traditional economies are based on subsistence. Whether through hunting, fishing, gathering, or farming, subsistence is based on a mutually beneficial relationship between the environment and the community (LeBlanc, 2014). This worldview holds that the land, animals and people all share a common essence and are treated equally and respectfully (Simpson and Driben, 2000).

Different from capitalism, which exploits natural resources, the traditional economy treats consumption as a reciprocal exchange that benefits all parties, supporting healthy and resilient ecosystems (McPherson and Rabb, 1993; LeBlanc, 2014). Researchers such as Abele and Southcott (2007) recognize that “much of the traditional economy of indigenous societies can be considered part of the social economy in that much of its pre-capitalist values still play an important role in the region and act in contradiction to the profit seeking values of contemporary society” (p.3). Resource extraction and accumulating private wealth is a primary goal of the Canadian Government and the capitalist system it is embedded within, which is very different from reciprocity, resource sharing, and mutually beneficial relationships that indigenous culture is built upon (LeBlanc, 2014). As part of colonization, a market-based economy has been imposed on the Indigenous peoples of Canada (Driben, 1985; Kuokkanen, 2011).

Project Overview

Foraged food has been part of the human diet for thousands of years, but with the advancement of agricultural techniques that are capable of feeding people on a global scale, traditional knowledge of how to provide oneself with sustenance from the wild is becoming less common (Johnson and Earle, 2000). Gone are the days where everyone produces or gathers their own food, as a majority of people buy their food from grocery stores, participating in a market-based economy. Many Indigenous peoples continue to harvest wild blueberries as part of a mixed economy that blends the traditional economy and a market-based economy to provide the community with monetary income and food (LeBlanc, 2014). Through the blueberry, this case study examines the social economy of food in Northwestern Ontario.

Some forest foods such as the blueberry have become commonplace in grocery stores, albeit they are cultivated varieties and expensive to purchase. In Northern Ontario, wild blueberries are a highly nutritious fruit that are gathered by people as part of an annual seasonal cycle during the late summer and early fall. The blueberry is a prolific native plant in the boreal forest of Northwestern Ontario that is highly abundant and has been available as a resource for food security 9,000 years (Dawson, 1983). Recent archaeological excavations outside of Thunder Bay have provided evidence—in the form of tools and campsites—that Indigenous peoples have occupied the area for a minimum of 9,000 years (Russel, 2012).

In Northwestern Ontario, foraging for blueberries and other forest foods occurs largely on Crown land (i.e. land that is owned and controlled by the Government of Canada), and is perceived to compete with the dominant forestry industry, which focuses on extracting timber resources from public lands (Milne, 2013). Baldwin and Sims (1997) suggest that forest foods are a possible source of economic development and Milne (2013) further believes that blueberries throughout the Boreal Forest Region are a viable economic development opportunity. Currently, local forest food entrepreneurs who are competing with large-scale forestry companies to use the same land are severely constrained because policies, market opportunities, and access to capital are designed to benefit large businesses (Mcbain and Thompson, 2011; LePage and Jamieson, 2011).

This case study examines four blueberry foraging initiatives in Northwestern Ontario to demonstrate how foraging is an emergent part of the social economy (see Figure 1 for a map of the four case study sites). The first explores Aroland Youth Blueberry Initiative (AYBI), where community members harvest and sell blueberries to support programs for youth in the community. Second, Arthur Shupe Wild Foods is a commercial operation, which sells blueberries through the Dryden Cloverbelt Local Food Co-op. Third, the Nipigon Blueberry Blast festival, provides opportunities for individuals to pick their own blueberries and participate in a variety of other activities. Finally, Algoma Highlands Wild Blueberry Farm and Winery is the first and only privately owned commercial blueberry farm in Northern Ontario. Hence Algoma Highlands has emerged as an important opportunity for food social enterprise in the north, where over 90% of the land is crown land and extremely difficult to access for local food initiatives that require a land base.

Figure 1 — Map of four blueberry initiatives

Methodology

The research was primarily conducted by William Stolz, a self-proclaimed forest food forager with a passion for forest foods. Having previously worked at Ontario Nature to rekindle awareness of forest foods to Northern Ontario, William has conducted guided forest food walks and entrepreneurial workshops surrounding the creation and promotion of forest and freshwater food businesses. Through his experiences, he has built a network of forest food contacts across the province and embarked on this research as part of a more detailed, academic inspection of the forest food economy of Northern Ontario.

The sites for the four initiatives were selected based on two main criteria: diversity and geographical scope. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with knowledge holders from the four different blueberry initiatives and all interviews were audio-recorded.[1] Interview participants included: Arthur Shupe, Owner/Operator Arthur Shupe Wild Foods; Norma Fawcett, Co-Founder, Nipigon Blueberry Blast Festival; Sheldon Atlookan, Aroland First Nation Band Councillor and Representative, Aroland Youth Blueberry Initiative; and, Trevor Laing, Owner/Operator, Algoma Highlands Wild Blueberry Farm and Winery.

1) Aroland Youth Blueberry Initiative

Aroland First Nation is located in Northern Ontario, approximately 90 km north of Geraldton and 25 km west of Nakina (see Figure 2). The community gained reserve status under the Indian Act in 1985, with reserve lands totalling 19,599 hectares (Matawa First Nations Management, 2017). Aroland has an off-reserve population of approximately 400 people (Matawa First Nations Management, 2017) and an on-reserve population of approximately 366 people. The community occupies 3.21 square kilometres of reserve land (Statistics Canada, 2017). The residents of Aroland are on average a younger population with 35.6% under the age of 15, 61.6% between the ages of 15 to 64, and only 4.1% aged 65 or older (Statistics Canada, 2017).

Aroland First Nation is a part of Treaty 9 (1905), which protects the community’s right to practice traditional activities throughout crown land within their traditional territory (Matawa First Nation Management, 2017). The community is located along the Canadian National Railway line and was named after the Arrow Land and Logging Company settlement that was previously located on the land which the Aroland First Nation reserve currently occupies. The Aroland First Nation traditional territory is a highly productive source of blueberries, providing a secure and accessible supply that exists under the community’s authority (S. Atlookan, personal interview, November 16, 2016).

Figure 2 — Map of Aroland First Nation on the highway network (Matawa First Nations Management, 2008).

In Aroland, berry picking is a way of life that can be traced back many generations. Gathering blueberries was part of a larger nomadic subsistence lifestyle where migration with the seasons occurred as they followed the available resources (LeBlanc, 2014). Berries were an important part of this process because they provided nutrition through the winter and were gathered on fishing or hunting trips, as part of the traditional lifestyle. Elders from the community remember that in recent history berries have been sold to rail workers, train passengers, neighbouring Ojibwe and Cree communities, and even to Minnesota as a dye for blue jeans (LeBlanc, 2014).

The Aroland Youth Blueberry Initiative began in 2008 as a social economy initiative, when community members tried to sell their surplus berries as a fundraising activity to help their youth (The NAN Advocate, 2012). The community formed a non-profit depot where people could sell their berries to the AYBI. Discussing the benefits of the AYBI, Leblanc (2014) states:

We have observed its positive contributions to the local community as it has expanded to become a resilient and effective community food hub. This initiative created a sustainable social enterprise that enables the exchange of social, environmental, and financial capital within our community. This social enterprise is unique to us in many respects—it is voluntarily managed, sustainably self-funded, and connected to Ojibwe culture and traditions (p 133-134).

Local food hubs can be considered self-organizing complex adaptive systems (CASs) that interact within the industrial food system on multiple levels, as they emerge, organise, grow, and innovate within a complexity framework, shaping each other’s evolution (Stroink and Nelson, 2013). The AYBI food hub consists of a complex group of interacting elements which, when combined, display properties that are unpredictable, but greater as a whole, instead of as separate pieces. In other words, a combination of interconnecting factors led to the creation of the AYBI, but without all the pieces, the results may not have been as successful and the initiative may not have been created.

Nowadays between approximately late July and early September, blueberries are picked by the community for use as part of a reciprocal network, which includes family members, the elders they care for, and the AYBI. Some pick for themselves and the AYBI at the same time. Picking for the ABYI occurs on a voluntary basis, but the pickers are compensated monetarily for their efforts, at below market prices. This enables the community to benefit from the AYBI on multiple levels. Berry pickers make a few dollars that can help cover the costs of transportation to the berry patch, while the AYBI acquires berries that are sold in many locations throughout the region, helping to raise money for the youth of Aroland.

Blueberries are brought back to the community warehouse where they are inspected and purchased daily by AYBI volunteers from within the community. As many blueberries as possible are purchased and the berries are transported in an air-conditioned van, keeping the berries cool during transportation to other communities. Berries are sold to buyers in Thunder Bay, such as private grocery stores, restaurants, the Thunder Bay Country Market, and the Thunder Bay Regional Health Sciences Centre Food Market. Other First Nations such as the Red Rock Indian Band assist the AYBI by selling berries at their First Nation Gas Bar, at no charge to the AYBI.

Currently, the ABYI sells berries in the region through local food markets, roadside stands and at other First Nation communities located closer to the TransCanada highway in order to fund youth programming in the community of Aroland First Nation. The youth initiative buys equipment for the community, such as baseball gloves, bats, balls, safety equipment, and floor hockey sticks. Purchasing equipment helps those who could not afford it otherwise and provides an opportunity for the youth to become motivated and participate in recreational activities. This social, cultural, and ecological initiative appears to have emerged through self-organization within the community. The AYBI is community-based and community-driven, with community knowledge, a traditional lifestyle, and health and well-being as central themes.

The AYBI is structured to operate with minimal infrastructure, supporting a hassle-free environment for the community to sell berries. The current format only requires berry pickers, baskets, and a vehicle to transport the berries to other communities. The berries are all wild, lowbush blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium, nigrum var., and myrtillus) that are handpicked. While the annual productive capacity of local blueberries controlled by the community is greater than what is currently picked, many community members feel that growing into a larger business might result in increased government rules and regulations, which is not desired. For example, becoming a business requires a business licence, and selling berries in a grocery store requires adherence to additional health permits, health inspections, packaging, and labelling regulations. The current process does not require pickers to follow occupational health and safety regulations; there are no age limits, no sign-up sheets, no supervisors, and no hours of operation. This format supports First Nation autonomy and Indigenous food sovereignty, allowing Aroland First Nation to decolonize their food system through a decreased dependence on the global food system, bringing back a traditional way of life that is at the heart of what it is to be Indigenous.

The AYBI established a set of goals to guide the initiative. These goals aim to “build leadership and entrepreneurial skills in the community’s youth and that the Indigenous worldview inform our actions” (LeBlanc, 2014, p.137). The AYBI embodies an Indigenous worldview by following the following criteria (from (LeBlanc, 2014, p.139):

- This initiative is undertaken through collective actions;

- We are sharing opportunities with each other;

- The labour and knowledge of pickers are respected through engagement as equals;

- We demonstrate reciprocity through fair prices paid both to the picker and by our customers;

- We provide real world experiential learning opportunities for our community; members to build practical skills that support life in this place; and

- We seek advice from local knowledge holders and we honour our responsibility to all creation by not taking more than we need

In 2012, the AYBI was honoured with a Community Food Champion Award from Nishnawbe-Aski Nation as the largest supplier of handpicked blueberries in Northern Ontario and their estimated revenue generated that year was between $30,000 and $50,000 for the community (The NAN Advocate, 2012).

Barriers

Transportation is the largest barrier for the AYBI, because the distance between communities in the region is so great and the vehicle transporting the berries travels back and forth between Thunder Bay and Aroland at least twice a week—which is very time consuming, when a return trip takes over eight hours.

Aroland is attempting to reduce aerial glyphosate herbicide spraying within their traditional territory by informing the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) of where they will be picking berries and for how long. They have asked the MNRF to not spray these areas until after the blueberry season has ended because it is “…devastating for the blueberries and for the pickers of Aroland and others around the area” (S. Atlookan, personal interview, November 16, 2016). Aroland has been successful at reducing the spraying in the area and they are working to eliminate spraying in the future.

2) Arthur Shupe Wild Foods

Arthur Shupe took over wild low bush blueberry picking from his parents in 1995, and now employs seasonal berry harvesters near Dryden, Ontario. He has been selling wild low bush blueberries to Thunder Bay through Belluz Farms for over twenty years, and recently began selling through the Dryden Cloverbelt Local Food Co-op and to contacts in Winnipeg, Manitoba. He also picks cone seed, chanterelle, and morel mushrooms. Arthur Shupe prides himself on a reputation for having very clean berries: “customers have told me they can take my berries and pour them right out of the basket into the pie shell” (A. Shupe, personal interview, February 27, 2017). Having clean berries is so important to him that he has designed a unique berry-cleaning device that he keeps secret from the public.

Shupe employs an average of eight to ten blueberry hand pickers that travel to blueberry patches surrounding the town of Dryden. These berry camps can be up to 300 kilometres away from town. He inspects the berries the hand pickers bring him, and will not buy wet or slap-picked berries because wet berries are bruised, and bruised berries do not keep for long periods. Slap-picking involves slapping the tops of the blueberry plants to knock the berries into a container, which causes bruising and then the clusters of berries near the ground are usually stepped on. Shupe has developed his own effective method for berry picking that he shares with his pickers as a trade secret. He hires pickers of all ages and has been known to offer hitchhikers that are passing through temporary work. Arthur Shupe does have competition from other berry pickers but they know each other and they split the available resources through a mutual agreement, generally staying away from each other’s camps.

Shupe processes the berries and transports them to different businesses where he sells them in bulk. He also sells any surplus berries on the roadside at different locations throughout Thunder Bay. Recently the demand for blueberries has become so great that he has barely been able to fill the bulk orders, leaving fewer berries for the public to purchase. He sells his berries for $35 for a four-litre basket, even though other pickers have told him that his prices are too low. He believes in providing an affordable product for the public because he recognizes that not everyone has access to nutritious food and he wants people with lower incomes to be able to provide their families with blueberries.

Shupe recognizes blueberry picking gets people outside where they can breathe clean, fresh air while they are camped out in the berry patch. “It’s relaxing because you’re away from the hustle and bustle and stress of town; you’ve got clean air” (A. Shupe, personal interview, February 27, 2017). He also acknowledges that blueberries are nature’s health food because they reduce medical expenses, help to detoxify the body, and are under-recognized since new medicinal benefits are continually discovered.

His business also practices sustainability, which is why he requires his berries be handpicked, because he has seen the effects of using berry scoops firsthand. He has found that using the berry scoops pulls the plants up out of the earth and breaks their hair and main roots, which sets the plants growth back and can kill the berry plants if used too many years in a row. Another sustainable activity conducted by Arthur Shupe is leaving the area cleaner than when he started picking.

Anything that can be recycled is recycled. The garbage goes into the landfill so it is like I say, respect for the land is a major issue with me… at the end of the season I always take a garbage bag around the berry patch picking up litter. Some of it’s been there for two, three, four, five years…I still go out and try and leave the place cleaner than what it was when I showed up (A. Shupe, personal interview, February 27, 2017).

Barriers

Finding a reliable berry picking crew remains the biggest challenge that Shupe has encountered. At first, he had a single family that would faithfully pick for him each year, but circumstances happened where they stopped picking for him. Nowadays he has begun to use different websites such as the Dryden Cloverbelt Local Food Co-op website to recruit berry pickers, in hopes of reaching a wider audience.

Spraying of herbicides has also affected Shupe’s blueberry business as he has seen entire patches of berries wiped out by spraying. “I hate the fact that the mills spray defoliant because once the defoliant is sprayed there isn’t a blueberry plant in that patch” (A. Shupe, personal interview, February 27, 2017). Although there are tensions between forestry companies and blueberry pickers, Shupe did approach Resolute Forest Products and asked them to stop spraying a 300-acre patch of land that had the perfect conditions for blueberry growth. The forestry company obliged him and for five years, they held off spraying the area. Despite tensions that exist around herbicide spraying, it seems there is a voluntary willingness on behalf of both parties to cooperate in sharing forest resources. Another connection between forestry operations and blueberries is newly harvested pine stands where blueberries have a propensity to grow in the acidic soils provided by the pine trees.

However, it is getting tougher and tougher to find new blueberry patches because they are just running out of stands of pure pine. Like it’s just that simple, the best wood has been taken by the mills for the most part so you’re constantly getting further and further from the market to do the collection of the blueberries which is beneficial in one way because the amount of pollution in the ground is reducing (A. Shupe, personal interview, February 27, 2017).

It is this relationship between newly harvested forestry operations and berry picking that has caused Shupe to begin travelling up to 300 kilometres away from Dryden to find productive blueberry patches.

Transportation is a major barrier to selling blueberries for Arthur Shupe Wild Foods. Since his blueberry harvesting camp is up to 300 kilometres away from the town of Dryden, the price of gasoline adds additional expense, and the time it takes to travel adds another dimension to the fragility of the blueberries during transport. For example, Shupe mentioned that blueberries could not be flown reliably because the air pressure may bruise the berries. He also knows a person who transported berries from Northern Ontario to Toronto and had an entire shipment bruised from improper handling, as one large bump in the road can be enough to damage the blueberries, rendering them unsellable for regular consumption. There are still options for bruised blueberries, as they can be turned into jam or wine.

Lastly, climate change is on Shupe’s radar, as he recognizes that global warming could affect the wild lowbush blueberries at some point because hotter temperatures and drier conditions may cause the plants to die from drought. Late frosts have occurred recently and have become a serious issue in the last few years because the frost causes the blueberries to get frostbite, which lowers productivity.

3) Nipigon Blueberry Blast

The Township of Nipigon is located along highway 11/17, at the top of Lake Superior, beside the Nipigon River. Crossing the Nipigon River Bridge is the only way to travel across Canada through Ontario because there are no other roads that traverse the Nipigon River. The town has a population of approximately 1,600 residents and an area of 109 square kilometres. The Red Rock Indian Band and Lake Helen reserve is located a kilometre northeast of Nipigon, along Highway 11.

Norma Fawcett, an Elder from the Lake Helen Reserve, where the Red Rock Indian Band is located, had a vision of establishing a blueberry festival. Her purpose was to celebrate and honour the blueberry plant. The Nipigon Blueberry Blast formed when Norma Fawcett approached the Nipigon Chamber of Commerce asking for the creation of a blueberry festival to honour the blueberry and its significance. In an interview with Norma on January 05, 2017, she spoke about people not showing plants proper respect. Some people trample the berries, but as part of an Indigenous worldview Norma explains that people should respect all living things, and that someone else’s negative actions can affect others, so we should be kind and watch our language.

To bring awareness of the traditional practice of berry picking to everyone, in 2002, the Blueberry Blast formed under the auspices of the Land of the Nipigon Chamber of Commerce. In 2007, the Blueberry Blast was turned over to an independent committee of volunteers, which only lasted one year; however, a year later, the committee switched to a sub-committee of the Township of Nipigon recreation committee (Township of Nipigon, 2016) to support access to additional funding (N. Fawcett, personal interview, January 05, 2017).

The main objective for the festival remains, yet over time, the festival objectives have been expanded and include (Nipigon Blueberry Blast, 2016):

- Honouring the blueberry and encouraging awareness of a locally available food source, while respecting the environment

- Making Nipigon a destination during the event and attracting tourists to Nipigon while encouraging repeat visits, creating a positive impact on existing local businesses

- Positively impacting community spirit by involving both interest groups and businesses

- Providing a morale booster through entertainment, activities, food, fun, music and dance

- Encouraging participation and interaction of all age groups

Blueberry Blast participants pay an entrance fee to participate in the festival and are provided with an opportunity to pick blueberries at a nearby berry patch. Community members and visitors have an opportunity to have fun, get to know one another, and harvest nutritious berries. Providing access to blueberries is an important function of the Blueberry Blast.

The Blueberry Blast festival activities are held at the Nipigon Marina, with picking activities occurring east of Nipigon, off Highway 17, in locations that have been previously logged for timber. One location used before is Camp 81 Road. There are numerous logging roads in the area and the location contains a mix of sand, soil, organic matter, and exposed bedrock. The terrain varies from hills with scarce amounts of trees to swampy low areas.

The Blueberry Blast was embraced by the Township of Nipigon as a tourism event that provides a variety of activities for both local residents and visitors to the community. Past activities have included pancake dinners, children’s games, talent shows, a dog show, as well as vendor booths with blueberry pies and other products or information. The festival forges a collective community identity around a natural local food resource.

The Blueberry Blast was embraced by the Township of Nipigon as a tourism event that provides a variety of activities for both local residents and visitors to the community. Past activities have included pancake dinners, children’s games, talent shows, a dog show, as well as vendor booths with blueberry pies and other products or information. The festival forges a collective community identity around a natural local food resource.

The Blueberry Blast in Nipigon brings in tourists from neighbouring communities and beyond, as one of the few blueberry festivals in Ontario, but they have been lacking a blueberry vendor for some time. Recently the organizing committee invited the AYBI to the Nipigon Blueberry Blast. Guests at the Blueberry Blast have been asking for blueberries to buy for a number of years now, but there have only been limited roadside sales. With the addition of blueberries from the AYBI, consumer demand for blueberries at the festival may finally be satiated.

Volunteerism is a main aspect of the Blueberry Blast. One time a person in a canoe arrived as Norma and her life partner Bill were packing up the Blueberry Blast. The canoeist was a volunteer heading to the Red Rock Folk Festival and he came just at the right moment when they needed his help to pack away heavy items. “People just sort of came out of nowhere to help. It was beautiful” (N. Fawcett, personal interview, January 05, 2017).

Barriers

Transportation is a barrier that the Blueberry Blast has tried to address by including transportation as part of the festival for those who do not have a vehicle and cannot access blueberries without participating in the festival.

Foraging occurs on Crown land that is shared with forestry operations and causes a great deal of tension concerning the spraying of glyphosate to kill off competing tree and shrub species. This process requires the forestry company that harvest timber in an area to regenerate the trees to a predetermined height and quantity. To complete the process of regeneration, spraying of herbicides is conducted occasionally on the harvested areas to kill all broadleaved plants, allowing coniferous trees planted by the forestry company freedom to grow without competition from broadleaved plants. Since blueberries are broadleaved plants, herbicide spraying has a negative impact on the propagation of berry plants.

Spraying of blueberry patches by forestry companies is of great concern. In 2015, an Ontario Nature petition was circulated at the Blueberry Blast by concerned citizens and non-profit organizations, and was signed by most people in attendance[2]. The Blueberry Blast committee is in contact with the MNRF to ensure that spraying does not occur in Blueberry Blast picking areas.

4) Algoma Highlands Wild Blueberry Farm & Winery

In 2006, Algoma Highlands Wild Blueberry Farm & Winery formed when Trevor and Tracy Laing bought 640 acres of land just outside of Wawa that is situated in 100 percent pure sand from the ancient shores of Lake Superior. Wawa is located near the eastern shore of Lake Superior, along highway 17 and has a population of approximately 3000 people.

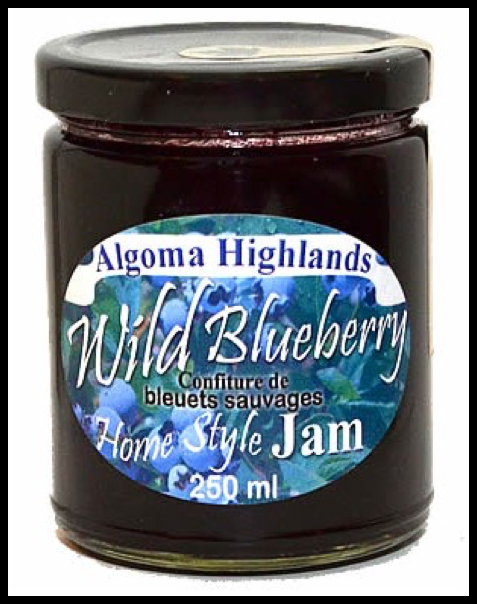

By 2011, they began to sell fresh and frozen blueberries and have since then branched out into value-added products such as blueberry preserves, barbecue sauces, and syrups. They own the first and only commercially operated wild blueberry farm in Northern Ontario that has emerged from tending naturally occurring blueberries rather than importing non-native blueberry varieties. Already they employ approximately 35 seasonal blueberry pickers on their farm, who are paid by the hour and per basket. Some of the pickers are tree planters who rotate to the farm after the tree-planting season is finished in June. This arrangement allows for an extended time frame for seasonal workers. The pickers use berry rakes and a few mechanical berry-picking machines. In addition to blueberries, the farm also includes raspberries, six acres of strawberries where customers pick their own baskets of berries, and there are plans to add rhubarb soon. All of these initiatives provide new sources of income for northerners where previously there were no non-timber forest jobs. These types of job opportunities add stability and sustainability to northern communities known for the constant cycles of boom and bust. In addition, Algoma Highlands aims to further assist in community building through its storefront by inviting local artisans to display and sell their arts and crafts. Algoma Highlands also contributes products to Cloverbelt Local Food Co-op which enhances access to a native northern local food sources.

By 2011, they began to sell fresh and frozen blueberries and have since then branched out into value-added products such as blueberry preserves, barbecue sauces, and syrups. They own the first and only commercially operated wild blueberry farm in Northern Ontario that has emerged from tending naturally occurring blueberries rather than importing non-native blueberry varieties. Already they employ approximately 35 seasonal blueberry pickers on their farm, who are paid by the hour and per basket. Some of the pickers are tree planters who rotate to the farm after the tree-planting season is finished in June. This arrangement allows for an extended time frame for seasonal workers. The pickers use berry rakes and a few mechanical berry-picking machines. In addition to blueberries, the farm also includes raspberries, six acres of strawberries where customers pick their own baskets of berries, and there are plans to add rhubarb soon. All of these initiatives provide new sources of income for northerners where previously there were no non-timber forest jobs. These types of job opportunities add stability and sustainability to northern communities known for the constant cycles of boom and bust. In addition, Algoma Highlands aims to further assist in community building through its storefront by inviting local artisans to display and sell their arts and crafts. Algoma Highlands also contributes products to Cloverbelt Local Food Co-op which enhances access to a native northern local food sources.

Algoma Highlands’ products bear the Foodland Ontario label and are sold in a variety of stores throughout Northern Ontario, which includes the Cloverbelt Local Food Co-op. They also ship as far away as Winnipeg and Toronto with a refrigerated reefer truck they own. Their blueberries sell to the public for 30 to 35 dollars a three-litre basket and in a year, they can harvest up to 100,000 pounds, with the potential to grow half a million pounds. Algoma Highlands started a winery and it is in the initial stages, as they have hired a winemaker to produce their first batch of blueberry wine for sale by the end of 2017.

They provide multiple benefits to the community such as hiring local workers, buying local goods and services, and paying taxes to the municipality. They have embraced tourism as a part of the farm and are looking at doing tours in the future. Scenic High Falls is a popular tourist destination located on the property, and numerous tour buses bring tourists to see the falls. A small retail store is in the works; and they expect to have local artisans display their works at the store.

Barriers

A manufacturing licence is required to operate a winery. It is an onerous process to acquire a licence because the paperwork is lengthy, detailed and requires the ability to understand the process and cope with bureaucrats, which may be difficult for some. As part of the licencing process the municipal, provincial, and federal governments are all consulted. Wineries are audited often. One Cloud North solely operates the winery, allowing it to be audited separately from the rest of the operations. The farm is incorporated as Level Plains, which owns Algoma Highlands Farms and One Cloud North.

Distance to market is the biggest issue. With no existing distribution system, they have to grow, harvest, market, and sell the berries—they do it all. They find it is getting easier now that they know where to market and sell their berries. Sales outlets include Cloverbelt Local Food Co-op and Willow Springs Creative Centre’s seasonal market. Moreover, they are increasing their value-added products because they are easier to move and have a longer shelf life, allowing for more year-round sales.

Distance to market is the biggest issue. With no existing distribution system, they have to grow, harvest, market, and sell the berries—they do it all. They find it is getting easier now that they know where to market and sell their berries. Sales outlets include Cloverbelt Local Food Co-op and Willow Springs Creative Centre’s seasonal market. Moreover, they are increasing their value-added products because they are easier to move and have a longer shelf life, allowing for more year-round sales.

To address the need for blueberry harvesters, they innovatively employ seasonal tree-planters who rotate to blueberry picking after the tree planting season has ended. However, harvesters remain an ongoing challenge. For additional workers, they are looking at bringing in foreign workers to help supplement their labour force and ensure maximum production.

Fluctuating climatic conditions have caused large variations in annual blueberry production. For example, in 2012, they did not get a blueberry crop and luckily, they were still in the development phase and therefore their losses were minimal. Already they have seen the annual harvest period fluctuate from as few as 15 days to as many as 30 days. To manage climate change they have been looking at the possibility of an irrigation system to keep the blueberry plants watered. Because they are a commercial farm, the federal government tests for crop pests such as blueberry maggot. Though the pest is only found in Southern Ontario because the winters in Northern Ontario are too cold for them to survive, the warming climate might allow the blueberry maggot to reach further north.

Social Economy Themes

In this section, we identify a series of common themes throughout the four case study initiatives that relate to the social economy of food.

People and the Land before Profits

Many of the social, cultural, and ecological values provided by berry picking are not recognized as having value in today’s market-based economy (LeBlanc, 2014), yet berry picking provides a mechanism for individuals to connect with nature on a holistic level, and assume a stewardship role. Many Canadians are facing issues related to poverty, homelessness, and hunger (Restakis, 2006). Bradley and Herrera (2016) recognize social movements related to community food security, food sovereignty, and food justice have arisen in response to the failures of the current multinational industrial food system to fairly and equitably distribute healthy, affordable, culturally appropriate food. These aforementioned movements work to decolonize the current food system.

In the four initiatives profiled above, there is a clear pattern of placing people and the land before profits. For example, the AYBI focuses on fundraising for the youth of their community through gathering berries. Emphasis is placed on the traditional activity of harvesting berries and the pickers are paid a small monetary compensation for berries they sell to the AYBI. This assists community members who may not be currently employed, and it provides an opportunity for berry pickers to better afford the costs associated with berry picking such as transportation. Though the pickers are making some money, the majority of profit goes back into youth programs and equipment for the community. The AYBI enables the community to practice traditional subsistence activities through a mixed economy. Through blueberry picking, the AYBI incorporates values for the youth around identity and connection to the land. They are taught traditional knowledge that is passed down from generation to generation around how to harvest and care for the berries in a good way.

Arthur Shupe provides his blueberries to the public at the lowest price he can because he believes that regardless of income people deserve the chance to eat highly nutritious, reasonably priced blueberries. Despite blueberry pickers urging him to increase the price of his blueberries, for the last five or so years Shupe has barely been making any profit from selling his blueberries. This has not deterred him from providing blueberries to the public in an ethical and environmentally friendly manner.

Shupe and his berry pickers attempt to be as environmentally friendly as possible, treating the plants and the environment with respect, cleaning up the campsites, and recycling all recyclable items. In the past, Shupe has employed tree-planters who work seasonally on the land, rotating from planting to picking blueberries as part of an environmentally conscious lifestyle. This is similar to Algoma Highlands Blueberry Farm and Winery where tree-planters continue to be employed as blueberry pickers.

Social Capital

Putnam (1995) describes social capital as “features of social organization such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit” (p.66). Connections are built while out on the land foraging. It is a way for people to build inter-generational relationships: having fun, sharing stories, talking, and meeting new people are all a part of the picking experience that helps to create and strengthen social networks. This leads to an increased sense of well-being.

Blueberry picking is part of the identity of many people in Northern Ontario as they connect with the land, and many have lifelong memories of picking berries as a child. An increased social network of trust is built between oneself, nature, and other community members. Through this social network, blueberry picking becomes the norm, a part of the annual cycle that mutually benefits the community as food security is increased and relationships with each other and the land are strengthened.

The Nipigon Blueberry Blast offers participants the opportunity to connect with nature and others by picking blueberries out in the wilderness. This coordinated event brings together people of all ages to enjoy the bounty that nature provides. Participants trust that they will be transported to a location that is teeming with ripe blueberries that can be picked and eaten in the following months. Through reciprocity, the Blueberry Blast committee trusts that the pickers will treat the land with respect.

Social Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Economic Diversification

During the Nipigon Blueberry Blast, demonstrating the importance of the blueberry to the community and tourists provides an opportunity for the diversification of food security strategies as well as economic development opportunities that differ from the predominant resource extraction industry in the region. The Blueberry Blast supports the tourism industry within the Nipigon area and the Blueberry Blast committee members have generated innovative ideas to continue to attract people to the region annually. Any committee member is able to add any activities they can plan to the festival, allowing social innovation to flourish. The Blueberry Blast festival also provides a venue for entrepreneurs to highlight their business through selling products at their booth, promoting a diversification of the economy.

Arthur Shupe Wild Foods and Algoma Highlands Wild Blueberry Farm and Winery are excellent examples of the entrepreneurial spirit that exists within the region. Both businesses have created ways to distribute blueberries widely throughout the region and beyond through building their own transportation networks. The AYBI also has created a transportation network.

The AYBI demonstrates a novel way in which economic diversification away from a traditional market-based economy can help to incorporate aspects of Indigenous culture through reciprocity and sharing into a community-based model. This model provides a means to decolonize the community’s food system and bring back traditional values.

Adaptive Capacity to Increase Community Resilience

The AYBI adapts to the yearly cycle of berries and adjusts community consumption depending on the quantity of berries available. Some years there are fewer berries to go around and some have to make do with little to no berries. However, the First Nations in the region have built a network in which they communicate with each other the environmental conditions in their areas. Communities with inadequate berry resources have an opportunity to get berries from communities that are having a good berry season through sharing, trade, or sale of the berries. This network enhances the opportunities that everyone who wants berries can access them, even if late frosts or a dry growing season reduced berry production in their specific picking locations.

Arthur Shupe Wild Foods navigates the many different regulations that arise through running a business. For example, he learned that there were limits to the amount of gasoline and propane that can be transported at any given time before requiring a dangerous goods placard on his vehicle. These regulations are the type of thing most of us would never even consider, but after more than 20 years in business many different situations have arisen in which he had to change his operating procedures to be compliant with government regulations.

Spraying chemicals as part of forestry operations has a large impact on the blueberry harvest and has become a controversial topic in Northern Ontario. Members of the Aroland First Nation, Arthur Shupe, and participants from the Nipigon Blueberry Blast have begun to push back against the current forestry management system through different means such as petitions and negotiations with the forestry companies responsible for spraying the herbicides with the goal of reducing the impact herbicides are having on our forest and our food supply.

Conclusion

Foraging for food brings people together and connects them to the land while building social networks, trust, and a reciprocal relationship. Foraging is an effective method for increasing food security because foods such as wild blueberries have a long history of use in Northern Ontario. Though it may be difficult for some to reach the berry patches, there is a desire by many to trek out into the wilderness and harvest their own supply of blueberries for the upcoming year.

Many forest foods have not been commercialized for a variety of reasons such as low yields, short shelf life, long growth cycle, and complex symbiotic relationships between the plant and other forest flora (Forbes, 2017). Policy and regulations also present significant barriers to selling forged foods in commercial markets. There is a growing demand for ethical, local, and functional foods. Often the recreational, aesthetic, traditional and cultural values of forest foods are viewed as more important than commercial values (Mitchell and Hobby, 2010). With the local food movement gaining prevalence, people are beginning to realize what the Indigenous Peoples of North America have known for millennia… there is an abundance of sustainable, nutritious, medicinal, and accessible food throughout the landscapes of North America.

References

Abele, F., and C, Southcott. (2007). The social economy in northern Canada: Developing a portrait. Paper presented at the 1st International CIRIEC Research Conference on the Social Economy.

Babbie, E. and L. Benaquito. (2002). Fundamentals of social research. Scarborough, ON: Thompson Nelson.

Baldwin, K.A. and R.A. Sims. (1997). Field guide to the common forest plants in Northwestern Ontario. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Thunder Bay, ON: Field Guide FG-04. 359 pp.

Bradley, K. and H. Herrera. (2016). Decolonizing food justice: Naming, resisting, and researching colonizing forces in the movement. Antipode 48(1): 97-114.

Dawson, K.C.A. (1983). Prehistory of the interior forest of Northern Ontario. In A. Theodore Steegmann Jr., ed., Boreal forest adaptations: The northern Algonkians, New York, Plenum Press, pp 55-84.

Driben, P. (1985). Aroland is Our Home: An Incomplete Victory in Applied Anthropology. AMS Press, New York. 121pp.

Forbes, D. (2017). Beginner’s guide to foraging and better harvesting methods. Retrieved from http://wildfoods.ca/blog/beginners-guide-to-foraging/

Johnson, A.W. and T. Earle. (2000). The evolution of human societies: From foraging group to agrarian state. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. 440pp.

Kirby, S. L., L. Greaves, and C. Reid. (2006). Experience research social change: Methods beyond the mainstream: Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press.

Kuokkanen, R. (2011). Indigenous economies, theories of subsistence, and women. American Indian Quarterly. University of Nebraska Press. 35(2): 215-240.

LeBlanc, J.W. (2014). Natural resource management and Indigenous food systems in Northern Ontario. Doctoral Dissertation, Lakehead University.

LePage, D. and A. Jamieson. (2011). Complex Community Issues: how does social enterprise help? Paper presented at the Fourth Canadian Conference on Social Enterprise, Halifax, Nova Scotia, November 20-22, 2011.

Lewis, M., and D. Swinney. (2007). Social economy? Solidarity economy? Exploring the implications of conceptual nuance for acting in a volatile world: BALTA B.C.-Alberta Social Economy Research Alliance.

Matawa First Nations Management. (2017). Aroland First Nation. Retrieved from http://community.matawa.on.ca/community/aroland/

McBain, E. and M. Thompson. (2008). Profile of Community Economic Development in Ontario: Results of a Survey of Community Economic Development across Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.ccednet-rcdec.ca/files/ccednet/Profile_of_CED_in_Ontario.pdf

McPherson, D.H., and J.D. Rabb. (1993). Indian from the Inside. Centre of Northern Studies, Thunder Bay. 55 pages.

Milne, R. (2013). Exploring wild blueberries as a place-based socio-economic development opportunity in Ignace, Ontario. Masters Thesis, Lakehead University.

Mitchell, D. and T. Hobby. (2010). From rotations to revolutions: Non-timber forest products and the new world of forest management. BC Journal of Ecosystems and Management 11(1 and 2): 27-38.

Nipigon Blueberry Blast. (2016). About us. Retrieved from http://nipigonblueberryblast.com/index.php/m-about

Putnam, R.D. (1995). “Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital.” Journal of Democracy 6(1): 65-78.

Restakis, J. (2006). Defining the social economy – The BC context. British Columbia Co-operative Association. Retrieved from http://bcca.coop/sites/bcca.coop/files/u2/Defining_Social_Economy.pdf

Russel, M. (2012). The Mackenzie I Site. Toronto Chapter of the Ontario Archaeological Society Newsletter. Profile 29(1). Retrieved from http://toronto.ontarioarchaeology.on.ca/Profile%2029.1%20Feb2012.pdf

Simpson, L.R., and P. Driben. (2000). From expert to acolyte: Learning to understand the environment from an Anishnaabe point of view. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 24(3): 1-19.

Statistics Canada. (2017). Aroland 83, IRI [Census subdivision], Ontario and Thunder Bay, DIS [Census division], Ontario (table). Census Profile. 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001. Ottawa. Released May 3, 2017. Retrieved from

http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

Stroink, M.L., and C.H. Nelson. (2013). Complexity and food hubs: Five case studies from Northern Ontario. Local Environment 18(5): 620-635.

The NAN Advocate. (2012). NAN in the news. Retrieved from http://www.nan.on.ca/upload/documents/pub-advocate-dec-2012.pdf

Township of Nipigon. (2016). Blueberry blast. Retrieved from http://www.nipigon.net/business/business-directory/festivals/blueberry-blast/

[1] All interviews were held in person between November 2016 and March 2017. We received approval from the Lakehead University Research Ethics Board in August 2016.

[2] Will Stolz worked for Ontario Nature at the time and was the person at the booth gathering signatures.